|

|

The Old St Beghian | |

| July 2025 | |||

A Privileged Life

Recollections of Foundation House, St Bees School, in the 1960s

Peter Royds (2025)(This is Part 1 of Peter’s recollections; Part 2 will follow in the next Bulletin)

Privileges

Throughout my time at the school, from 1962 to 1967, and long before that, privileges were an interwoven feature of everyday life at St Bees. Boys who became prefects acquired a host of privileges together with a degree of personal authority which is difficult to imagine today. If you were good at sport, you were given privileges and accompanying colours and badges for all to see. Some privileges were conferred simply through progression up the school. But however you got them, privileges represented status and recognition.Foundation – Day 1

In complete contrast, junior boys, aged 14, arriving on Foundation House after their initial year at school on a ‘Waiting House’ (Meadow or Eaglesfield) had no privileges and no status. They were all ‘fags’. The first evening on their ‘Main House’ saw them lined up in the junior dayroom where the eight or so House Prefects, in order of seniority, each selected his ‘private’ fag for the year (three terms). The rest became ‘general’ fags. Throughout this process, the fags remained silent and were required to continually look deferentially at their feet. This was the start of four years on Foundation. It was a long way from home.

There were perhaps 90 boys on Foundation, about twice as many as on each of the other two main houses, School House and Grindal. Foundation was nominally divided in two – North and South – but only for sports activities and because this division conveniently created four house teams when it came to ‘house matches’. But essentially, Foundation North and South were administered as one house, with three housemasters.The School

St Bees village is tucked away on the coast of Cumbria (then Cumberland). St Bees School was well known as the school with short trousers for all boys, aged 13-18, at all times. There were no day boys. It was a minor public school with a proud rugby heritage. The school was founded in 1583 by Archbishop Grindal.

There was parental contact only once or twice each term if and when parents visited, and by letter.

No ‘phone calls unless you went up to the village ‘phone box. No T.V. Most of us

were well accustomed to living without parents until the holidays, having typically already spent five years at prep. school from the age of eight.

At school, everyone was called by their surname, or nickname, some friendly, some derogatory. When I now read about a contemporary or near contemporary in the OSB Bulletin, his first name can, as often as not, come as a revelation. The cleaners and catering staff were referred to as the ‘skivs’.The Privileges Test

After their first week or so, the new arrivals on Foundation were given a privileges test – the ‘Priv Test’. You had to pass it or re-sit until you did. The test was supervised by a prefect and held in ‘Big School’, a large, tiered classroom within Foundation. This was not a trivial matter. Privileges were firmly part of the culture, as illustrated later. The test involved a lot more privileges than I now remember. It may even have included reciting the names of the 1st XV rugby team, the school’s most venerated elite.Those in Charge

The housemasters did not concern themselves with such matters as fag selection and privilege tests.

In general, their involvement in the day-to-day house routine was not front line. The detachment was not unlike that of senior army officers, working mainly through the prefects.

They did, however, attend lunch with everyone in Foundation dining room. They later took the daily evening house assembly and prayers where they made announcements and voiced encouragement or disapproval, as required. At the end of each day, a master would accompany the two ‘duty prefects’ round all the dormitories to oversee ‘lights out’.

Operational law and order was left to the prefects. It was a lot of unsupervised authority to give to this group of 18-year-olds. Fifty years earlier, no-one would have questioned the wisdom of handing young men this level of responsibility and status in preparation for military or colonial service. The model hadn’t been adapted to life in a different era.Routines

Each of the six or seven dormitories on the first floor had a prefect in charge of it, with two in the biggest dorm – ‘Big Dorm’. There, a prefect slept at each end of the very long, airy, almost barrack-like room with rows of iron-framed beds and white porcelain wash-hand basins down the sides. There were sentry-type clothes’ cubicles beside each bed. This was the senior dorm.

The prefects could stay up later and had a bedtime mug of Ovaltine, or similar, in the ‘Nag’s’ (matron’s) surgery. They could also get up later in the morning, except for the two duty prefects who had to be first up again to tour the dormitories on the wake-up round.

Every house had its own matron and ‘Sick Room’. Foundation also had a lady who sewed – all those woollen socks. She was a big woman and was known as ‘Zep’, for Zeppelin.

The private fags might run a morning bath for their prefects in the prefects’ bathroom. They laid out his clothes for that day, together with the blazer they had brushed and the shoes they had polished.House run

Next, came the pre-breakfast house run. The prefects were exempt and ‘Senior Studies’ were too.

All the Dayrooms, apart from ‘Swees’ (explanation later) lined up along the walls of the wide stone-floored corridor in Foundation which ran alongside Big School and the four studies. Starting with the junior dayroom, we filed outside through the main door beneath the clock and into the quadrangle. We jogged left down the main road, turned left again via an iron swing gate and along the pathway at the side of ‘The Crease’ (the 1st XV rugby and 1st XI cricket field) to the bottom of the wide flight of steps leading up to The Terrace. At the top, on each side of the steps, the ubiquitous duty prefects had stationed themselves, ready to identify dishevelled hair or clothes, dirty shoes etc. Punishments were given for a repeatedly unkempt turn-out.More routines

The morning runners proceeded to the Foundation dining-room for breakfast. The non-duty prefects came down in their own time. No masters were present. After breakfast, it was bed-making to the prescribed standard. The weekday routine would then involve organising your books to take to classes, Chapel (‘The Shed’) at 8.30 am for morning prayers, three morning classes, a break back on house for drinks, a jam sandwich and change of books; two more classes, lunch, sports, two afternoon classes except on Wednesdays, tea, Prep’. Finally, the evening house assembly, with roll-call; and bed.Meal Times

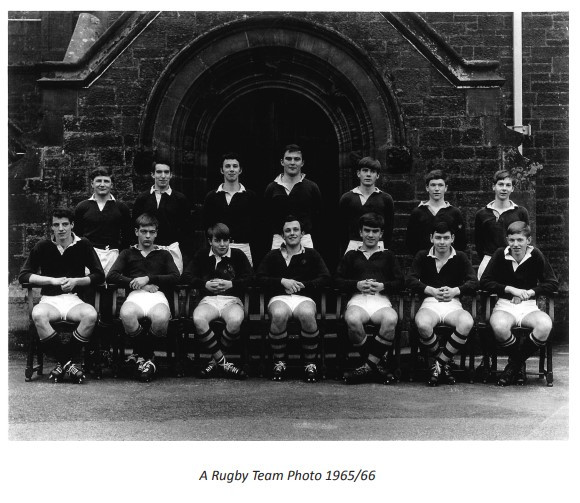

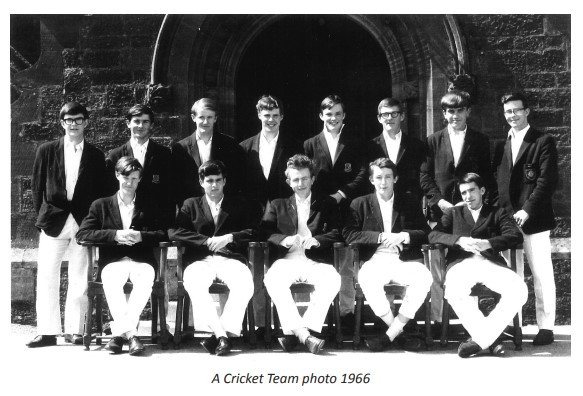

All meals on Foundation were taken in the dining-room. This was a long room with tables and benches down both sides and generations of boys’ names carved into the surrounding wood panelling, above which hung team photos. It was quintessential public school and happened to be the oldest part of the school.

There were two doors to the dining-room. Both were at the near end but on different sides of the room. One was the privileged door for the masters and prefects; the other was for everyone else. Down at the far end of the room was the top table, with chairs, for the masters and prefects. They entered the dining-room by their own door and walked down the middle of the room between the silent ranks of boys standing at their bench seats. No-one sat down or spoke until the Grace had been said.

We occupied more or less the same place at table for every meal but there was a degree of displacement at lunch-time when the ‘waiting house’ boys ate on their ‘main house’. Seating at the tables below the head table was in seniority order ending with the juniors nearest the second-class door. Everyone had a jar of jam and sugar, with name labels on them. These came out for breakfast and tea on wooden trays which were stored on racks in the wall.

Grace was said again at the end of lunch. There were versions in both English and Latin. Boys’ heads remained respectfully bowed as the masters and prefects processed out again between the silent ranks, as they had entered, and towards their designated door. Everyone else filed out after them, in seniority order, and through the non-privileged door. It was a mark of enforced deference to seniority that everyone more junior kept their head bowed and eyes to the ground until it came to their turn to move off and out. ‘Feet’ – i.e. keep looking at them – was the command given to any head raised prematurely in the dining hall before the more senior boys had yet to pass by.

Around the school, junior boys generally whose gaze rested too long on someone more senior were liable to be told to ‘turn it off’. It meant ‘know your place’. Nor did any junior speak to a much older boy without being addressed first. It was ‘being gassy’ to speak uninvited.Assorted privileges

As well as the Foundation dining-room, access to and from various other places about the school was regulated by privilege. Being allowed to walk across The Crease wearing ordinary shoes, rather than rugby or cricket boots, was a very elevated privilege. Other examples were walking through the main gates, opposite Barony, onto the Terrace in front of Foundation; maybe also sitting on some or all of the wooden benches along the Terrace. One of the two main entrance doors to the Chapel was a privileged door.

In Chapel, there was a service by the school’s own chaplain every morning, except Wednesday when it was School Assembly in the Memorial Hall. Attendance at morning Chapel and Assembly was mandatory, as were the Sunday morning, and also evening, services in Chapel. Holy Communion, held before breakfast, was an optional third Sunday service for boys who had received Confirmation. The school choir occasionally sang at Late Evensong in the village Priory Church, always an uplifting setting.

Watching the school 1st XV playing against visiting schools on the Crease was also obligatory, rain or shine. Cheering ‘On School’ was expected and not joining in showed a lack of school spirit. Everyone stood along the Crease touchline. Wooden duck-boards were put down if the ground was soft. It was a privilege for certain boys to watch from the Terrace, with the staff. There were no football teams at St Bees. The school took a rather sniffy view of the game. ‘Gentlemen’ only played sports as unpaid amateurs in these days, not as professionals.

It was a privilege to wear the school scarf without a coat. And only the Upper Sixth form could wear distinguishing white stripes on each lapel of their blazer – upper sixth stripes. There might have been privileges regarding who could use certain seats in the library, depending on their proximity to the fireplace.Clothing and Sports Hierarchy

The school uniform, worn every day, consisted of a navy-blue blazer and shorts, lighter blue socks, and a white shirt. Ties were worn only on Sunday. It was cool to wear faded socks, handed down from previous generations. Socks were required to remain pulled up to below the knee and secured by garters. The blazer badge bore the school motto ‘Expecta Dominum’ – ‘Await the Lord.’ New kit was obtained from the school shop in Barony and Zep sewed on the name tags and badges.

Members of the 1st and 2nd XV and XI who were awarded their ‘colours’ could wear them all the time on their blazers in place of the ordinary school badge. An even higher award for first team rugby was a tasselled cap and, for cricket, a striped cricket blazer. There were also cravats. These more decorative awards were worn chiefly in team photos.

School colours and ties were also awarded for athletics, which included distance running, fives, squash, tennis and swimming. Athletics colours were not displayed on the blazer. They were sewn on a white long-sleeved athletics jersey. The Crease was marked out as a running track for Sports Day.

When the powers that be made these school team awards, they were posted on the sports notice board in the main corridor of Foundation which was a well-used thoroughfare for the whole school. This was also where the school team selection lists were put up for home and away matches – 1st teams, 2nd, 3rd, Colts, Under 15’s, the Running 8, etc. Some fixtures involved an overnight stay. Rossall School, in Fleetwood, was an overnight fixture, as was King William’s, Isle of Man, travel to which was by air.

As well as the school team awards, there were house team awards. Each House had its own distinctive award ties for excelling at senior or junior ‘house matches’. Grindal House had only the one generic house tie for both levels. There was also an award of games socks somewhere in all of this. If you hadn’t been awarded a house or athletics tie, you wore the standard school tie on a Sunday.To be continued in the next Bulletin...

Home

The St Beghian Society

St Bees School,

St Bees, Cumbria, CA27 0DS.

Tel: (01946) 828093 Email: osb@stbeesschool.co.uk

Web: www.st-beghian-society.co.uk

![]()